Should academic publishing be flipped upside down?

I have recently been watching Sabine Hossenfelder's videos and her thoughts about academia's state. Although her main focus is on physics and the lack of new ideas in the field, I see almost the same situation in my field—a totally broken system with no space for innovation on the verge of collapse.

It is hard to pinpoint a starting node in this entangled situation, or maybe it is hard for me to find it as I am kind of new to this sector. The list of items that pop into my head are publishing, egos, hierarchies, traumas, and silence.

So let's start in that way.

Publishing

Source: 愚木混株 Yumu

The publishing structure made sense in the 1800s and 1900s, probably up to the 1930s. You write your experiments and findings, send them to a journal that makes the connection to other scientists, and ask them to review whether the written paper is innovative and contributes to the expansion of knowledge. The journal editor receives these recommendations and sends a letter to ask the author to reply and adjust, and the author (or their university) pays for publishing. Finally, the journal includes the article in a periodical publication that is printed by a publisher that groups the different journals, and it is distributed to other researchers who are subscribed to the journal. This is still the way it is done... kind of. And on the theory, it makes sense.

Back then, it was quite an effort to send the letters, receive the commentaries, send letters back, do the editorial work of adjusting to the journal printing structure, and all the editing part of it, print, and then deliver the printed magazine to different universities. So, to help in this process and keep the review process's objectivity (This is the main aspect not to change), reviewers do this job for free, in their own time, which usually means working extra hours. Up to the 1930s, the costs were supported by a loop of readers, so your institution paid a subscription, and you could publish there and get in return other authors' publications; additional readers would pay for each issue and help finance the publication process. It's kind of what you do if you subscribe to NatGeo magazine. The costs paid to the publisher were for printing, mailing, and editing.

In the 1930s, a print-per-page fee started appearing, and authors were asked to contribute to the printing and dissemination costs so libraries and readers wouldn't be burdened with rising subscription costs. The thing is that if you pay to be published, you are seen as an advertisement. Or would you pay for a magazine with only Rolex, Dior and Cruises pages? This is usually the added/extra part of a publication. They pay for being there.

Therefore, some publishers kept the subscription model, and authors were not paying for publishing; the reader assumed the cost all the time. Guess which model authors preferred during the following years?

Later, around the 80s, things turned into full-on businesses. Do you want to read an article? Subscribe. No other way. So, the authors were not paying anything; both the costs and the profit came from subscriptions. The big publishers absorbed small ones, and today only a few set the rules. Elsevier, Springer Nature, Wiley, Taylor, and Francis, etc, started getting big and controlling the prices. They set up the bar of accessibility. Can you pay? You get access. "Oh, you can pay? Maybe you can pay more".

Source: Huntorganic, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Starting 2000s, and with the internet getting full strength, the idea of open access started pushing up. Why limit access to information to those who can pay? At the end is the taxpayers' money. So, things started to flip.

To make journals open-access, someone has to cover the costs. And if the reader is not gonna be the one who pays, it will be the author who does. The pay-per-page model no longer made sense as many articles were put online and not printed anymore. So, at the beginning, publishing an article could cost around 500 to 1.500 dollars.

The idea seemed to work; people prefer to read without access restriction, and the costs were acceptable for universities and research institutions. However, the power was already concentrated in the big publishers. The tradition and prestige of publishing in their journals gave them the opportunity to set up the rules at any time.

So in the following years prices were rising up. The $900 average rose to $1600 in 10 years (2011 - 2020). A 117% rise. However, averages here are a lie. There are thousands of journals. And the majority do not have a high score. Authors don't prefer to publish with them. So, most of the authors go for above-average publications. The median and mode values are around $2000. And this is kind of the minimum of what you are expected to pay if you want to be part of the club.

Prices kept rising, supported by the idea of open access. Do you want to know how much it costs to publish a gold open-access paper in Nature in 2025? 12.690 dollars!!!

Source: Arthur A

But keeping this process in the XXI century makes no sense, at least for me. Now, the editor asks for suggestions of potential reviewers and kind of forwards your email to them. Reviewers quickly check and reply to the email back their comments (for free) with a deadline always ticking. Then, comments are forwarded to the author, and another email goes back to the editor with the final "camera-ready" article. It is, most of the time, up to the author to do all the editing work and adjust the article to the journal's guidelines, and it won't go forward if it does not comply 100% with these guidelines. So, where is the editor's work?

Once things are set up, the article is published in a PDF file and on the publisher's website. The cost? Hosting the PDF and HTML, and indexing them in a database. Still, prices are rising.

Ranking scientist

The number of publications and citations that an author has has become the way of measuring the "success" of a scientist. Therefore, there is pressure to publish and publish more, so you would rank higher on a number of publications and increase your chances of being cited. The quality of the content is not that important, and it is assumed that the peer review has taken care of it. But if everyone needs to publish and is in a hurry for their own work, you will feel empathy and, probably unconsciously, approve what you read and focus more on the structure rather than the content.

You are always reviewing content from your field, which is a pretty normal thing to do, but as the quality of what you read goes down, your bar as a reviewer starts dropping, and then more and more useless research gets published.

At the same time, journals are ranked by number of citations, so if you publish in the same journal over and over again, and others also do it. Citations will easily increase. So the concentration becomes important to rank higher.

Likewise, researchers are measured by the number of publications in these highly cited journals and by the total number of citations. So, if you ask your friends to cite you, or you cite yourself with another first author covering your tracks, you can get your scores higher and make sure you are not fired from your job regardless of the quality or behaviours you have in the other parts of your job (e.g. teaching, supervising, relationships with your students or coworkers).

Many times, to secure that your numbers go up, you are asked to include a known author from your institution as an author, regardless of whether they work with you or not. Also, you are asked to cite this and that, which will help the number of your friends. Probably you have been asked or suggested to do so already. It is a pretty standardized practice. That, in my view, should not exist.

While all these practices keep existing, the ranking numbers and "successful researcher" measurements will keep being a lie. It is like Twitter, the first one to post, the most retweeted, the most liked.

Egos

As publishing and citation numbers are the ones that mark how many chevrons, stripes, and bars you have in your uniform, these numbers easily inflate people's egos.

"Top 5% most cited scientist in my field", "h-score of 100". Numbers that measure frequency, but never quality. Nonetheless, you get more stripes and want to be respected (or idolized in some cases).

Even when you are a young researcher with not many publications in line egos can start building with soft pats in our backs. Think of this: You attend a conference (which you pay to be in🙄) and present whatever it is you are working on. Your conference is full of people who, just like you, are going to present. You all are in the same field, and no one wants to put holes in the other side of the boat. At the end, you are all in the same ship. So you get a "Thank you for your amazing presentation. It's a really interesting research" loop where you get patted on the back and then you pat someone else's back. A perfect circle of praising each other and inflating our own egos.

Keep going to conferences, and you will easily start believing you are the best of the best. I mean, your peers are praising you. Heroes thanking heroes. Kings praising kings. It must be that the gods gave us the right to rule.

The issue comes when people start looking at others as if they were inferior. "I am a god, you are a student who comes to me for knowledge. If I find you worthy I will rise you to hero (masters programme) and if you survive the trials (PhD journey) I will name you Demi-god (Doctor) and you can start making your way into our kingdom, so when I retire you can take my place as a god in this realm"

It is a question of reverence, praise, and endurance. Persevere in this crazy world, and maybe you can get into academic heavens.*Terms and conditions apply; not everyone is guaranteed a place. Mental health breakdowns could occur. If the symptoms persist, consult with your doctor.

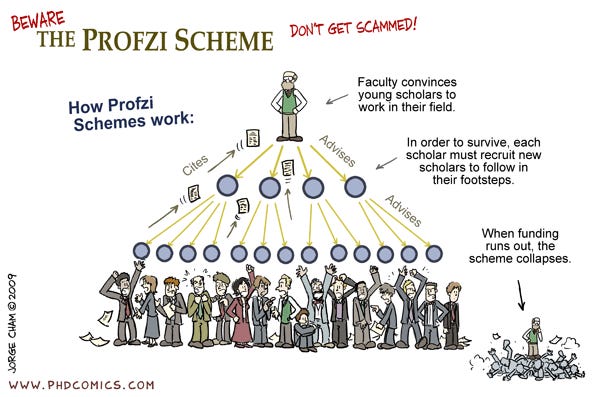

So it becomes a cult, a pyramid scheme where each level has its own ego point requirements. How many XP points does your ego bar have?

Hierachies

As academia works like a pyramid, there are several levels of hierarchy that are silently respected and even feared.

Source: Jorge Cham

Maybe you remember a teacher from high school who you were terrified to speak up in their lecture, the teacher no one wanted to ask a question to because they looked quite intimidating.

That's kind of the deal here. People don't dare to talk up. Yes, the socialization aspect is horizontal; everyone talks with everyone, no matter the rank. But when it comes to work, people restrain themselves. PhDs have a hard time saying stuff to their supervisors, Assistant professors do not raise their voice to associates, associates do not do it to full professors, and full professors don't say anything to deans or rectors. There is always an "I don't want them to get pissed with me" kind of thought.

The thing is that the ones above you can decide what is researched and what is not, who gets promoted and who does not, who is a valuable asset to the faculty and who is not. This creates a huge blockage for your career, and the only way to go up is to play this game, do not question much, smile, and nod. In a few years, if you have stayed in your place on the chain of command, you may get a better position. Just remember, "Do not dare to question my authority. After all, I am the expert here".

Trauma

Keeping your ground and not speaking up, nodding to everything even when you disagree has its cost.

Academia is hard. Most of the PhD have mental health issues; professors are at the edge of burnout collapse, people work on holidays to compensate; researchers are constantly applying for a grant to make sure there is a next job, you kind of need to do the work before you apply for the grant as there won't be enough time to complete the deadlines, and deal with everything: find funding, project management, literature reviews, experiments, be the coffee delivery person, send invitations, find your travel conferences, arrange your accomodation, keep accountability, etc. It is like being a freelancer but attached to a university—lots of stress.

You must go to conferences, create your posters, prepare lectures, teach, grade, supervise, go to social events, do more experiments, submit papers, get rejections, be the editor, apply to another journal, and find another job—lots of stress.

The result: resentment and rage (I'm writing this post out of anger and disappointment)

And, as there is not much mental support, everyone is going through the same, and previous experiences have not taught academics anything, the resentment has translated into a normalized suffering. "I suffered in my PhD, is okay that you suffer with yours" This phrase was an actual one that I was told when I complained about the stress.

My questions: At which point is it normal to suffer for a job? Are we going to keep letting this trauma pass to the next generation of researchers?

Silence

This is where I get most enraged—the silence.

Everything I am telling you is not new. Everyone inside academia knows this. Everyone has experienced a bit of it or all of it (including sexual harassment, bullying, plagiarism, sabotage).

But no one says anything.

If you do, you will be going against the hierarchy, against the status quo, and the "you are tripping your own career".

What many people do is just step off the sinking boat. The rate of young researchers quitting or changing careers is increasing. And even with people quitting, no one says anything.

In the best case, if someone speaks, the reply will be "Yeah, I know. It happened to me also. But there is nothing we can do". What a bullshit answer. The mediocrity, the resignation, the exasperation.

I know this because I spoke, complained, and asked for change—empty ears. I'm at the bottom of the pyramid. I can be ignored. We PhDs are seen just as another student, not a staff member—a cheap, temporary labor force. In 3-4 years someone else will replace us.

My proposal

So, what to do to try to change stuff? I would start from the token of trade. Publications. From there, a chain of effects.

First, the publishing system. Why do we need, in 2025, a concentration of articles in a few publishers? Each university can hold its articles using a decentralized open-source protocol. Many servers, authenticators, and reviewers are all in a peer-to-peer system, university to university. If you are as old as I am, think of BitTorrent but for research papers.

This system would dramatically reduce the costs, the peer review system will stay in place (at the end, no one is paying the reviewers), and the profits can be distributed inside the same system. Stop being a transfer tool of taxpayers' money to publishers.

Source: GuerrillaBuzz

Second, the authorship. If we want institutions to survive, institutions should have a larger role in the picture, without reducing the visibility of individuals. I would even include the CREDiT statement at the beginning. Not at the end, when no one is reading anymore.

This change will, in time, have an effect on the egos of the people. It is no longer important if you included Prof. Dr. Whatshisname in your authors. It is the institution that matters. Or tell me, do you cite UN documents by the long list of authors? Or, do you do it by the institution? e.g. UN-HABITAT? What about OpenAI or Google? Do you cite them by the authors or by the institutions?

I believe this focus on institutions can have an effect on the way we do research. As individuals are less important, it is easier to work in groups. Instead of 25 projects for a department of 20 people. Maybe it can be 10 projects with a larger impact and better collaborations. Less number of publications. More meaningful ones.

Let me show you how that would work:

Doesnt change much. But it changes everything.

Third, speak up: We need platforms and ways that protect the integrity of academia. This peer-to-peer system can also work as a way of marking up authors who recycle, plagiarize, or misbehave without the fear of consequences. No more NDAs if you speak up. No more silence from the management, if something bad occurs, this should be published.

Why do they hurry to publish a paper, but not when a professor is found guilty of sexual harassment? Why try to find "amicable solutions" when there are manuals and protocols for keeping up with academic integrity?

The whole system requires a change, but the first one is up to us. We need to speak up, recognize our strength, and also our responsibility to keep the ship afloat when the captain is trying to crash us against an iceberg. Speak of poor management, force bad captains to step down on command or leave the ship. Otherwise, Universities will sink.